Dizziness: new discoveries from Sunnybrook Research Institute

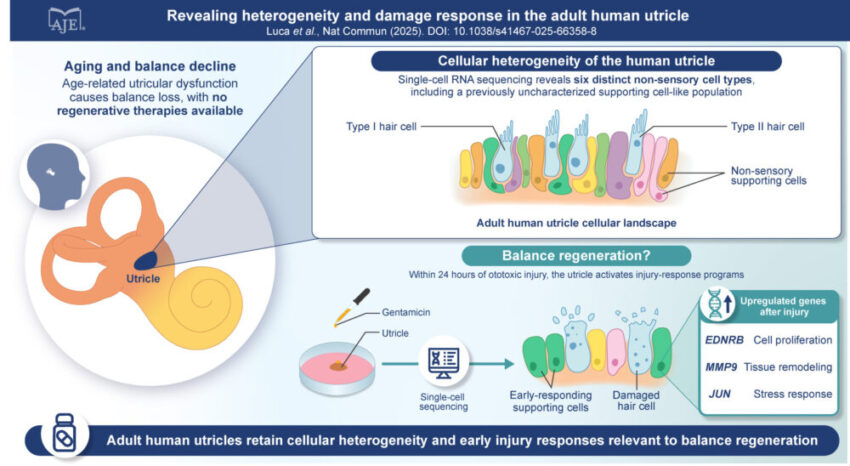

TORONTO – A team at the Sunnybrook Research Institute in Toronto, led by Italian scientist Dr. Emilia Luca, has for the first time mapped the diversity of cells in the adult human utricle, a balance organ of the inner ear. The team also discovered how this organ responds to damage, opening new avenues for developing future therapies to improve balance disorders such as dizziness, a leading causes of falls, especially among older adults.

To fully understand the importance of this discovery, it is first necessary to highlight the fundamental role of this small and often little-known organ. Every step we take, every head movement, every time we stand up, the utricle works silently to keep us stable, providing the brain with information about how we are moving, much like a navigation system. Trauma, disease, or medications such as certain antibiotics and chemotherapy drugs can damage the sensory cells of this organ, causing debilitating dizziness, increasing the risk of falls, and impairing everyday activities.

Currently, there are no treatments capable of repairing or regenerating the utricle, in part because studying the adult human inner ear is extremely challenging due to its limited accessibility. The new research led by Dr. Luca represents a significant step forward. By analyzing utricles donated by patients undergoing surgery, the team—comprising researchers from Professor Alain Dabdoub’s laboratory and otolaryngology surgeons at Sunnybrook Hospital, Dr. Joseph Chen and Dr. Vincent Lin—created a gene map of the cells of this organ and observed their responses to chemically induced damage within the first 24 hours.

As explained in the article recently published in the scientific journal “Nature Communications” (here), the study revealed a surprising variety of supporting cells—the “guardians” of sensory cells—potentially capable of initiating regenerative processes. Six distinct cell types with unique gene expression profiles were identified, along with more than 400 genes whose activity changes in response to damage. Notably, two groups of cells appear to act as “first responders,” activating genes involved in tissue repair and inflammation control near damaged areas.

“This molecular map shows us which cells may respond to damage and how we might stimulate them to regenerate the balance organ,” explains Dr. Emilia Luca, who has worked for years as a research associate in Dr. Alain Dabdoub’s laboratory. The latter, a professor at the University of Toronto and senior author of the study, adds: “These findings highlight previously unknown genes and potential drug targets, offering a roadmap for future therapies for balance disorders.”

The study also underscores the importance of hospital-based research. The analyzed samples came from patients rather than animal models, allowing researchers to observe biological processes directly in human organs. As a result, the data obtained—difficult to obtain in other contexts—contribute to more reliable findings and may have a tangible impact on the understanding of diseases and the advancement of treatments.

Dr. Dabdoub’s laboratory is now working on a comprehensive gene atlas of the human inner ear, which could accelerate new discoveries in the fields of hearing and balance. “These discoveries bring us closer to therapies capable of improving the lives of people with inner ear disorders,” concludes Dr. Luca, who is also president-elect of the International Association of Italian Researchers (AIRIcerca) in Canada and a member of the scientific committee of IMOBIO (Integrative Multiscale Open Biology Community).

In the pics above, Dr. Emilia Luca and Dr. Alain Dabdoub

Insights here: https://research.sunnybrook.ca/2026/01/inside-the-inner-ear-revealing-the-bodys-balance-organ/